Reckless associations: The ruling class creates new legal theory to stifle free speech

05/02/2022 / By News Editors

In a forthcoming article at the Harvard Journal of Law and Technology, three law professors propose a novel, legal tort theory of liability. This liability is referred to as “reckless associations,” and it has the effect of allowing a victim to sue a third-party for assuming a leadership position in an association if a member of the association intentionally caused harm to the victim.

(Article by Mitch Nemeth republished from Mises.org)

The professors proposed this secondary liability to crack down on social network agitators that have escaped legal punishment for their content, which they allege falls short of conspiracy and/or incitement. This theory’s immediate effect would be to flood the judicial system with lawsuits purporting to hold wrongdoers accountable. The secondary effect would be to pressure social networking platforms to maintain key network surveillance data readily available for plaintiffs’ attorneys.

The obvious flaw in this legal theory is that it attempts to fix a problem that only affects a very small fraction of all social network users. Though these users make up a fraction of the entire network, they were “central and active nodes in a dysfunctional network—one that has actually and foreseeably caused epistemic failure and resulted in conduct that harmed people outside the network” before the platform’s content moderators banned their accounts. For years, the platforms have maintained community standards and other policies to address content that may be illegal or objectionable. These policies exist to deter the types of content being addressed by the tort.

Progressives and many legal professionals claim that the existing social network environment is inadequate and does not address the real-world harms caused by a small fraction of highly engaged users. This secondary theory of tort liability was drafted to address this perspective and to work around the existing obstacles within the legal system. The First Amendment protects a wide range of speech and association, and section 230 of the Communications Decency Act protects platforms from civil liability.

While individuals may already be prosecuted for conspiracy and incitement, these legal theories “often fail when applied to group leaders who were not giving explicit orders in real time, or themselves committing crimes.” This tort similarly targets the inherent challenges of imposing civil liability on platforms rather than on individuals. Section 230 was implemented, in part, as a response to the challenges of content moderation on platforms. Congress’s intention was to “allow online services to moderate content on their platforms in good faith, removing harmful or illegal content while still providing a forum for free speech and a diversity of opinions.” Congress attempted to balance content moderation to deter civil liability and the fostering of an open, digital “public square.”

While the existing legal ecosystem is imperfect, it has allowed a wide range of perspectives to flourish. Institutions, individuals, and ideas that were once not notable now are given an equal playing field with more established institutions, individuals, and ideas. Of course, this can be problematic to established institutions, as it creates necessary competition in the battle of ideas. The article authors call out right-wing influencers like Alex Jones, Infowars, and members of QAnon, saying that platforms like Twitter essentially create an even playing field between them and legacy authority figures. Though this may be true, the “marketplace of ideas” is foundational to the First Amendment right to free speech.

“Reckless association” would cause two major externalities: 1) this secondary theory of liability would deter “intensive participation and engagement in online networks” and 2) the social networks would be required, under court order, to provide extensive metadata to plaintiffs’ lawyers.

Reckless Associations as a Deterrence Mechanism

The most obvious implication to free speech is that social network leaders “will be less inclined to take or remain in a position of influence” if “leaders know that there is a chance that they will incur the costs of litigation and a possible damages award.” As the authors state, “The implicit logic of contemporary debate is that courts cannot reach central nodes of a radicalized network without causing a chilling effort…. While this is true—l[i]ability will cause individuals to avoid becoming authority figures in groups that aggressively traffic in zany theories.” The authors intend to use tort liability to deter even a mere association with what they determine to be a “radicalized network.”

As an example, let’s say that a prominent Austrian economist is a central node within a network that opposes central banks. There may be individuals within that network that oppose central banks to such a level that they discuss ways to dismantle the central banks. A small fraction of those individuals may even consider violent action or perform violent acts against prominent central bankers.

Under this theory of liability, victims of such violence may be able to sue that Austrian economist for speaking in devout terms against the continued existence of central banks. If this were allowed, it would have a “chilling effect that would inhibit speech and free association.” Central actors or nodes would have to individually vet nodes within their network to deter radicals; this is unlikely to happen, so the effect would be to deter association with controversial ideas entirely and thus stifle debate within a small Overton window.

Surveillance Powers Handed over to Plaintiffs’ Attorneys

As the authors acknowledge, this theory of liability is possible because of advancements in artificial intelligence and network analysis. The platforms would have to share metadata with the plaintiff’s attorney through a court order. The attorney would have to prove each element (language bolded below) of the tort using that metadata.

The tort’s specific language is as follows: “A defendant is subject to liability for a plaintiff if the defendant assumed a position of leadership within an association that recklessly caused a member of the association to intentionally harm the person of the plaintiff.” Proving causation could present a challenge, but “this problem could be overcome with the right sort of data—if plaintiffs’ lawyers are able to access and analyze a meta-network of the third-party actor’s communications across multiple media and platforms,” write the authors. This analysis could prove technically and legally challenging, though it is likely that this same type of analysis is being done by intelligence agencies and law enforcement.

Social networks have been key actors in law enforcement investigations into terrorist activities and other illegal/illicit activity. As Lawfare notes, “Platforms now collect and analyze intelligence on a variety of threats, often in cooperation with law enforcement.” This partnership is strong, in part, because of constitutional and legal constraints, as well the fact that “private companies are generally nimbler than government agencies.” In a sense, these social networks are already captured as tools of the national security state. Expanding their surveillance capabilities to the domain of civil litigation should not present a challenge.

These platforms are well equipped to receive and share data in large quantities. As previously discussed, the platforms maintain processes to share relevant information with law enforcement. Platforms such as Meta’s Facebook have sought to partner with financial institutions such as JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Citigroup, and US Bancorp. Public reporting has disclosed that these platforms have similarly cooperated with “keyboard warrants” and “geofence warrants.” These instances demonstrate that the platforms cooperate with law enforcement with minimal pushback. This level of cooperation raises concerns about the platforms’ willingness to share sensitive data with external actors.

Market Forces Have Handled the Issues Being Discussed

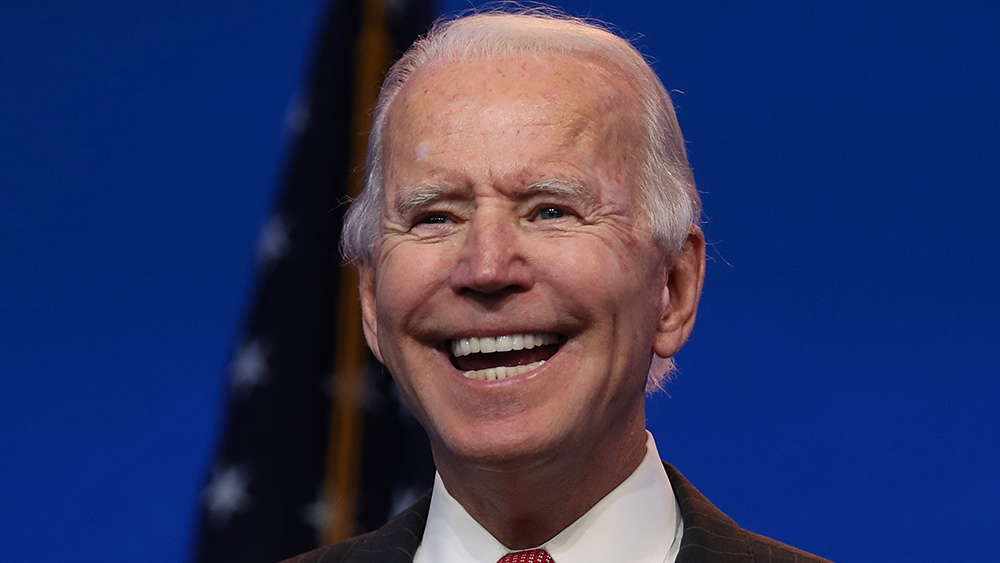

Aside from the two major consequences discussed above, this legal theory is unnecessary. The authors express a clear intention to target individuals like Infowars’ Alex Jones and former president Donald Trump. For years, both Jones and Trump have been under intense scrutiny and have undergone costly litigation. Separately, both individuals have been effectively blackballed from all prominent platforms. While one may disagree with the platforms’ rationale for banning these two individuals in lockstep, the market has proven to be responsive.

The platforms have responded to pressure from a wide variety of sources, ranging from elected officials to advertisers to special interest groups to their own employees. Unfortunately, the pressure has been to adopt increasingly censorious positions on content that does not conform to the mainstream narrative. Tesla CEO Elon Musk has taken note of this problem; Musk recently acquired a 9.2 percent stake in Twitter as a means to press the platform to adhere to fundamental free speech principles. Musk has previously stated, “Given that Twitter serves as the de facto public town square, failing to adhere to free speech principles fundamentally undermines democracy.”

Democracy requires individuals to be able to freely exchange ideas, which is why Congress drafted Section 230 as a shield against overreaching civil liability concerns. To address content that may pose a risk, the platforms already maintain community standards and other policies intended to moderate content. Facebook and Twitter employ thousands of content moderators, in conjunction with algorithms, to review content that may be in violation of policy.

The platforms partner with fact-checking outlets to assess the validity of viral claims made on the platforms. “It became a necessary feature of the new journalistic industrial complex in order to inoculate large tech platforms from government regulatory pressure and the threat of ‘private’ lawsuits from the NGO sector,” writes Tablet. Content shared on these platforms that is flagged as false or misleading gets downgraded by the platforms’ algorithms. While fact-checking organizations are frequently (and appropriately) labeled as partisan, this partnership supports the market-oriented approach to moderating content on these platforms.

This series of imperfect practices is best encapsulated in Twitter CEO Parag Agrawal’s recent statement: “Our role is not to be bound by the First Amendment, but our role is to serve a healthy public conversation and our moves are reflective of things that we believe lead to a healthier public conversation. The kinds of things that we do to work about this is to focus less on thinking about free speech but thinking about how the times have changed.” While imperfect, these market-led practices are preferrable to civil litigation and the accompanying surveillance architecture.

Conclusion

Civil liberties advocates would be keen to oppose this legal theory of secondary liability for the three reasons stated above: 1) reckless associations would cause a “chilling effect that would inhibit speech and free association,” 2) the theory would require platforms to provide a significant amount of sensitive network data to plaintiffs’ attorneys (many of whom could be politically motivated), and 3) the market has already taken steps to address the challenges of radical actors who may cause real-life damage.

This new theory will likely never become law in the United States, but it presents a useful visual of how First Amendment protections could be limited without direct encroachment. Separately, it demonstrates the authoritarian urge to use surveillance mechanisms to punish those deemed to be radical by the progressive establishment. Reckless associations is another attempt to stifle “arguments by people who believe they have a mandate of heaven, and the truth is whatever they say it is.”

Read more at: Mises.org

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

big government, conspiracy, fascism, First Amendment, free speech, freedom, insanity, intolerance, Liberty, lunatics, privacy watch, progress, reckless association, Social media, suppression, surveillance, tort theory of liability, Tyranny

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 PENSIONS NEWS